How to Remodel Reality with a Tall Tale

Writing a fantasy about a clash between art and nature

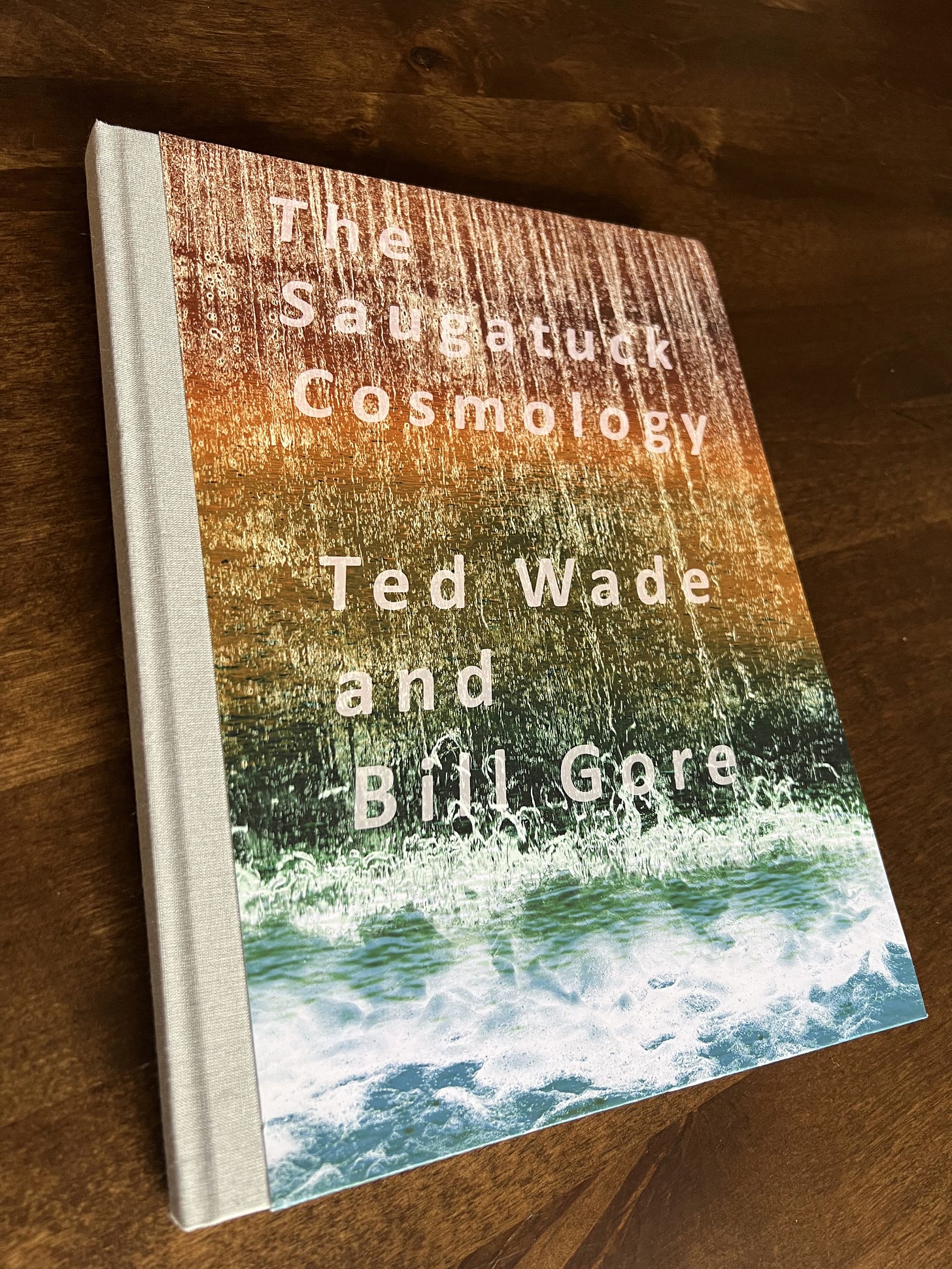

My artist friend Bill mesmerized me with a new collection of images. He became focused on the idea that an artist could imagine a different kind of world: so real that it could be visited in person. He wanted me to write the story of that visit and try to involve an AI in the project. We would combine the story and images “somehow.” Eventually, Bill’s metaphor of a conjured world as the embodiment of his artistic intuitions became a conceit, an 8,000-word extended metaphor for our relationship with nature.

Desperately Seeking Inspiration

Bill designs, prints, and binds books of his art by hand just for fun. We had tried the AI thing previously for another book of transformed photos. I learned then that asking an AI to write something imaginative is not even as good as asking a random stranger to write it. It won’t be what you needed.

For months I avoided the challenge. But Bill waited, and eventually, I had to be my own random stranger, tasked to make up a fantasy realm. It had to use Bill’s new collection of abstract images that were built from his photos of the Saugatuck River area. It would be populated with creatures yet to be described, having purposes yet unknown, and would reveal both the workings of their world and the adventures Bill’s new alter ego would have with them.

Talk about a blank slate. My story obviously should say something about art and creativity. It had to be a kind of fantasy, but there was no model for it. There was no genre whose conventions I could use, nor even any example of a story that was made up to explain a collection of abstract art.

A Glimmer

Maybe, I thought, the style could be like the sly, goofy ramblings of sci-fi author Rudy Rucker. I was also desperate for a plot device. I grasped onto Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass: an ingénue’s journey into a mirror world and a series of absurd encounters with strange, cranky creatures. Channeling Canadian comedian Red Green, I said: “I can do this. If I have to. I guess.”

Our assumption for what became The Saugatuck Cosmology was that an artist falls into an alternative reality that resembles the images he has been making. Imaginary worlds need to make some kind of sense, to be self-consistent. The SF trade calls it world-building. It’s because most readers want something more compelling and less like the illogical meanderings of a dream.

Some fantasies hardly connect with our world (AKA base reality) at all: as in classical high fantasy, like Tolkien or George Martin. Some fantasy worlds heavily overlap with ours, usually by being visible only to certain humans. Think Neil Gaiman or a zillion different vampire/werewolf tales. Other stories intertwine the two worlds, usually by having some characters able to move between them. That last became my situation, but it got complicated quickly.

System Requirements: what must be

The protagonist HA (Hero Artist) had imagined the fantasy world’s appearance, but nothing about its inhabitants. The fantasy creatures needed their purposes for existence — their own culture and history. Thus there had to be a rationale for this little world. Plus, there’s no story if you have no conflict. So we needed reasons for conflict between the artist and the creatures.

When I was still trying to pry something useful from an AI, Bill and I were trying to find the right level of conflict. The AI came up with ideas that resembled (what a surprise!) the conflict between AI developers and people. The creatures would be afraid of the artist because he invaded their privacy, distorted their reality, and was in some sense trying to remake their world. They might retaliate against this invasion. I could see this getting very intense, but Bill wanted to keep things more peaceful. As he said, “let’s move away from retribution and consequences.”

Still, the creatures couldn’t just be passive, somehow trying to tolerate whatever some random artist did or didn’t do to them. They and their world needed to have an obvious purpose and a complex causal connection with our reality. In that way, and unlike most fantasies, this one could be used to tell us why our world is like it is, by using dialog with non-human characters.

Bill kept me grounded by suggesting aspects that were necessary to our success, even if I was hung up on big issues like world-building. For example, he said, “I would like to have the creatures speak to us in their own voices as much as possible,” and they should be offering some kind of wisdom. Of course! To me, that meant that they had to be individuals with roles in their society that give them points of view, and they must know enough about humans to be able to talk about serious topics with one of us.

Bill and I had both been reading David Abrams' The Spell of the Sensuous, which argues that nature has voices that we can perceive. Not just metaphorical voices, but real communications from both organisms and inanimate things like terrain and weather. Some people who tune in find that they can learn to grasp or even join in those voices. Abrams’ most basic examples involve people who must hunt for food. They learn to read calls and signs from multiple species and participate in the conversations of predators and prey. So, we said, our fictional creatures should embody that communication with Nature, but taken to a new level because they could speak in human language.

Bill’s artistic process includes contemplation of the deep history of the land and its layers of life. This approach affects the images that emerge. We wanted to make the historical chronicle an explicit part of the story, a sort of living memory of the land.

My brain hurt trying to imagine what kind of reality would let us do all these things. The solution that finally held this all together was so radical that I thought of it as sort of cosmological. As in: if it were true then the ontological underpinnings of our reality would be different from our rationally scientific norm.

The Cosmology

I decided that the creatures are like the demigods of a polytheistic folk religion. That is, they are the spirits of everyday things and organisms. The spirits live in their separate world, but they animate and guide their mundane counterparts in our base reality. I called the spirits Ckami, as an homage to the pantheon of spirits (Kami) in Shintoism. This was a judgment call because I did not intend to borrow any more from that venerable and multi-layered religion.

The Ckami have a built-in conflict with humans because we have overrun and warped our world, the very one that the Ckami have shaped over eons of time. The weird twist is that their world, their “TrueReality,” is like the artistic vision of this one artist. Yet they’re the gods and he is just a guy, one random human. He cannot have created their world because they know that they created his world.

It’s a paradox that lets me take the story all over the place, with themes such as artistic creation, human relationships with nature, the purpose of life, and the source of the supernatural. I tried for seriousness overlaid with whimsy, as in: "How would Lewis Carroll and Rudy Rucker do it?”

To make it all work I had to invent enough details about their TrueReality to make it believable. I also had to anchor those details to what we can see in the wide variety of Bill’s images. To help with the latter, TrueReality consisted of three parallel phases, each looking different and having a distinct purpose. HA visits each of these phases, and as he does, the rhetorical temperature keeps going up, with wilder revelations about what is important and true in their world and ours.

Access

You can experience the story for free. To tightly integrate the images with the text, we used a cinematic technique in which the continuously scrolling story rolls over some pictures (like the opening scenes of Star Wars) and interleaves with others. Flowing images start you from a New England river spillway. You fall into imagined realms of first Water, then Stone, and then Air, until you pop back through the river’s surface into our base reality. Color is a part of the story, and even the background hues signal where one is in the story’s realms.

An illustrated book version is available, currently by special request.

Postscript: I learned that Rudy Rucker experimented with ChatGPT 4. He was "staggered and flabbergasted" about what it could do, though he did doubt that he would actually use it much.